Differentiating High Potential from Performance

How do you select people for promotion? Do your managers assess their potential based on past performance? If so your organization could be suffering from the Peter Principle – “In a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence”

There is strong logic behind this. Past performance does not necessarily indicate high potential, particularly if that future is in a significantly different role. The capabilities required to be a good engineer, analyst or researcher are quite different from those required for success as a manager. The traditional career path to CFO is a good example. The entry-level role of financial controller requires someone with an eye for detail, someone willing to check and recheck that the numbers are right. The finance manager needs people skills to monitor and control the team. And the finance executive needs a capability for strategic oversight. Each of these roles requires a significantly different skill set. That is not to say that an individual cannot develop each of these capabilities as they progress through their career. But it should be apparent that being a good financial controller certainly does not indicate that a person will make a good financial manager or executive. Yet most financial managers were promoted to their role because they were good financial controllers. With this approach it is easy to see how most people will eventually reach a role that they do not have the capability to do. A study by the Corporate Leadership Council, based on 11,000 managers and employees, concluded that while 93% of high potentials were also high performers, less than 20% of high performers had the potential for promotion. So, why the difference?

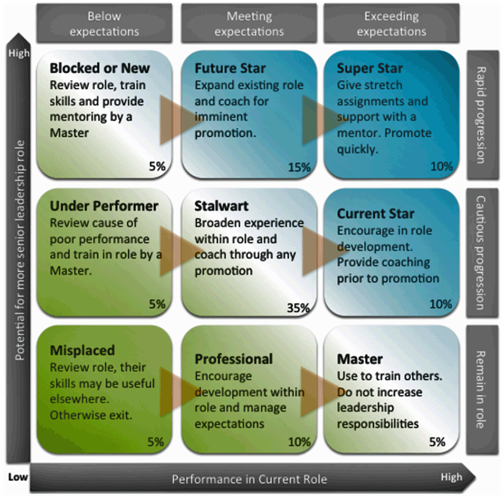

To combat the Peter Principle organizations try to focus on promoting based on future potential. But differentiating measures of past performance and future potential are not so easy. This is well illustrated when we plot our employees on a 9-box talent grid. The 9-box grid has been used by corporations since the 1970’s. Part of the attraction is the model’s simplicity which arranges every employee into one of nine types based on ratings of performance and potential. However, when we talk to many organizations, they tell us that their high potentials fail to live up to expectations. And when we take a look at their 9-box grids we find that people with a high performance rating are getting a high potential rating too. That goes against the Corporate Leadership Council’s study as well as our logic. What isn’t working?